Rugby Coach Weekly is the largest digital resource for youth coaches, trusted by 15,000+ coaches, teachers and parents every month.

Get access to

- 2000+ drills and games

- 350+ ready-made practice plans

- Expert coaching advice

- Training sessions for players from U6 to U17+.

Stopping the maul

Editor Dan Cottrell adds further context to two sessions.

Most driving mauls start from lineouts or from a kick off receipt. Gone are the days when we used them off scrums, but there are more instances of mauls being formed from rucks, especially after a dead phase.

Once a maul forms properly, the defenders know that the referee will give the attacking team two chances to move forward. If the maul stops twice then their 9 must “use it or lose it.” So, the defenders either have to commit resources to stop the momentum, or splinter the maul.

Therefore, the best form of defence against moving mauls is not to let them start moving in the first place.

Stop the “set”

Not allowing the maul to even get setup is great defence. If the tackler puts the ball carrier on the ground to start with then the maul can never start.

Even at lineouts the laws permit a team to “sack” a catcher. One player pulls the catcher to the ground as soon as their feet land. No other defenders should touch the catcher at this point otherwise it might be perceived a maul may be formed and the “sack” becomes collapsing the maul and a penalty kick.

See our practice on page 4 to build this tactic up.

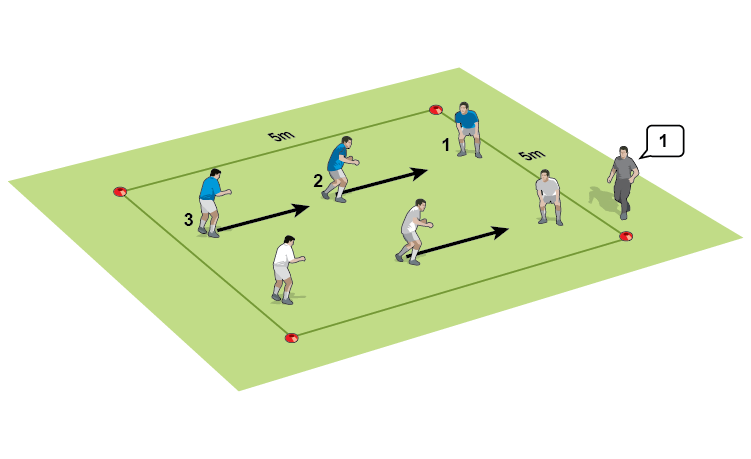

Isolate the ball carrier

Particularly with mauls that begin in open play, the initial blockers at the side of the ball carrier are slow at getting into position. Getting a defender into that gap beside the ball carrier can be the head of a wedge that can drive through the maul and split the ball carrier away from the bulk of their maulers.

Add weight – like a scrum

Even if a good “set” is made by the attackers, getting more bodies behind the ball before the drive starts can halt the maul in its tracks before it has begun moving.

To add weight effectively, the players should take up scrum positions. Don’t let them have their heads up.

If it is moving, then the players should drive into the maul, not just lean in and push. If they can work in pairs, even better.

Turn the tables

If all else has failed and the maul is starting to move, a higher risk strategy may be to attempt to use the attackers own impetus against them. Concentrating a drive against one side of the maul may spin the maul and leave the ball carrier at the rear exposed to a waiting defender (see isolate the ball carrier above) if fast enough, or at least the momentum may halt long enough for weight to be added subsequently.

This is not a tactic for close to the try line. It requires plenty of coordination between the players. In my experience, it works well for more established teams who have been used to using disruptive tactics before. They understand the mechanics and basics of stopping mauls and are open to new ways to do so. That’s why it’s a high risk strategy.

No-look passes risks and rewards

On page 7, we show you a variation of the “box” set up for a backs move. The idea is that the 10, or pivot player, releases a pass late, based on the call from the receiver who thinks they are best placed to break the line.

That sounds lovely in theory. Practising it under pressure shows that it’s never as easy as that because players not only have to see where the gaps are, they must communicate it and then execute it.

I’ve found that this needs a lot of patience from the players, and that’s not always in abundance in some training sessions where the players feel under pressure to perform. Though you want them to make mistakes, they still think that impacts on their selection.

Managing expectations aside, I think this “box” practice allows braver players to experiment with the no-look pass. It must be a short pass and the passer needs to know that the support player is racing onto the ball.

I advise players that the pass is best made thinking about where the defender can’t get to. So, if the passer steps right, and the defender follows them, then the pass goes left, and into the space. Otherwise the ball carrier holds onto the ball.

That should, in theory, make it easy for the receiver to know where to run. From there on, it’s a case of building a sense of confidence that both players know who’s going to be where.

I can’t think of how many times I said this to you at the end of an article like this, but I will still repeat it: Expect chaos and mistakes! Also, don’t make it a stipulation that the players use this type of skill in a match context. It’s a possible tool that might suit some players more than others.

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Colin Shaw

Gary Lee Heavner

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.