Behind the scenes with: England U18s

RCW editor Dan Cottrell studies the coaching methods of those charged with developing the next generation of England players, namely Jon Pendlebury, the England U18s head coach, and Will Parkin, his assistant. Dan outlines his eight key takeaways and what coaches at all levels can learn from the elite.

I was lucky enough to be invited to watch an England U18s training session, as they were put through their paces before their tour to South Africa, writes Dan Cottrell.

A total of 26 players and nine staff would be travelling to play three internationals, against Ireland and Georgia, as well as the home nation.

Jon Pendlebury, the England U18s head coach, and Will Parkin, his assistant, shared their thoughts and intentions regarding the direction training was taking.

There is so much all coaches can take from these sessions, even if we take into account I was watching the 26 best boys from England.

I looked at how simple the exercises were, when they are used, why they are used and the intensity and accuracy required.

Here are the eight key lessons I took away from my observation that I think coaches at all levels can use.

Be prepared

There are two themes around being prepared.

The first is how players experience international rugby and understand what the expectations will be.

This is to ensure that there won’t be many surprises if they get the opportunity to step up to the next stage, which might be an U20s game in the very near future.

For example, running out in an away game in France, with the home crowd at their noisiest, is to enter a cauldron of emotions. No training session can replicate that atmosphere. Any of the U18s who play in that game will be in better shape for next time.

This goes for routines and expectations. The morning I was there, four players missed a meeting time. They were lightly admonished this time and told that the U20s coaches would be more demanding.

The coaching group was keen to ensure that more experienced players helped less experienced ones with their preparations. For example: What do they need to know for training? What were the expectations about behaviour?

The second theme was about being prepared for the training session itself. We will look at that in the session design points.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

How can you help less experienced players feel their way into more stressful situations?

-

For matchday experiences, if a player can’t be on the bench and have some game time, they can shadow the team, perhaps acting as a water-carrier on the day.

-

Buddy systems, with more experienced players taking on a mentee, are a tried-and-tested method. Often, this is done informally, but an intentional plan with clear objectives is good.

-

Good mentorship builds good mentors for the future.

Pre-session information

With so little time on the training field, it is essential to make the best use of the available resources. Even at this level, there isn’t as much time on the grass as you might think.

There was an indoor meeting before the outdoor session started. Prior to that, the players were sent some video clips to study, which focused on the plays the team were going to implement.

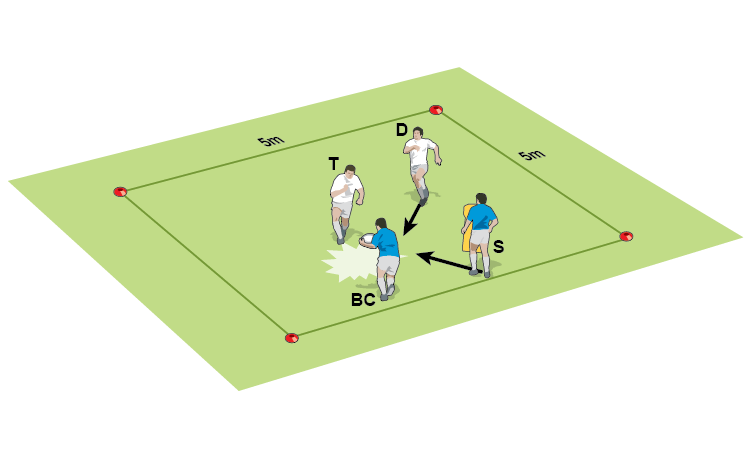

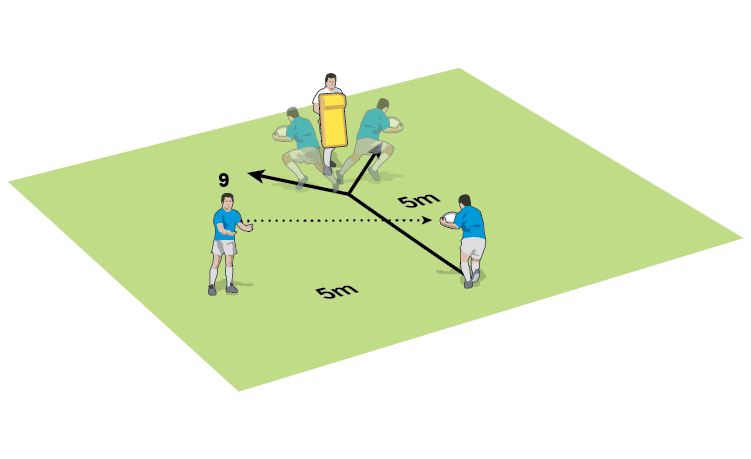

While there is structure on the pitch, the philosophy is that ’speed trumps structure’. In other words, everything should be done at speed, and, if the ruck ball is quicker than the players are at getting into their shape, the team plays anyway. The attack can’t give the defence the chance to reorganise.

Part of the speed comes from knowing the specific roles inside the structure.

The players studied footage from a lineout in a particular part of the field. It showed them running through the play in a previous training session, but it could, equally, have been from any team or any match.

This footage was replayed during the indoor meeting. The players, sitting in groups of similar positions, talked through where they should run and where to be from the subsequent phase.

For example, the last player in the lineout, who might have initially bound on to the side of the maul on the openside, would know that the backs might attack in the 13 channel.

The group would explore decisions based upon who carries when and where, and where that player from the maul may reload to attack for the next opportunity.

From these pre-set positions, the key decision-makers could look up, see where the defence was weakest and know where they could attack, with the confidence that they had options.

When the second phase of play unwinds, the video revealed how the timing might work. Some players might have been too deep, not engaging the defence if they were to be decoys.

Will Parkin asked the following questions to the group:

- What pieces of information do you need to know to run the play?

- How can you engage the defence here?

Players need to take ownership of the plays and the details in execution. For example, there was footage from games where it was clear when good footwork helped achieve better outcomes, or when an arriving player needed to latch onto another supporting player.

It was interesting that they discussed decisions around going in to support the breakdown, and the consequences on the next play.

For example, if the 13 had to resource a breakdown, that might change the angle of the next attack, because the shape of the attack was different.

Overall, while every phase of play aims to bust the line, players need to know what might happen next if it didn’t.

In this vein, playing out of your half from a set-piece might mean organising a good chase from a kick. A good chase needs the speedier players to be on their feet. It also depends on whether the kick is from the 9 or the 10.

Aligned with the philosophy of speed, this team was challenged to run/pass/kick from rucks and mauls in play, and explore what opportunities it created or forced.

The quicker into position in attack, the more likely you are to find a disorganised defence.

If this is the principle, it still needs planning.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

How much information can you share ahead of a training session? The first issue is whether the players will actually look at it. In that case, you can have two tiers of information: the first is need-to-know, and the second is nice-to-know.

-

What information would be helpful? Reminders of shared language, a play you’ve been running through, and perhaps a clip of a play or passage of play.

-

Make the information valuable at training. Challenge players on what they saw or thought about. Do it in groups, probably of similar positions.

-

When should you review the information? You can meet in the changing rooms before training. Five minutes here could actually give you more time on the field, because the players know what they are doing and why, and will have been part of the process of organising the plays.

-

Knowing a role, especially in supporting the next phase, can be explained away from the training session. Then, when the play is being introduced or reviewed on the field, the player might be able to understand what is happening and self-correct if they are out of position.

- Structure is a rule of thumb. It helps create a shared understanding of where to be and why during the first few phases after a set-piece. But, at a ruck, if the ball is available quickly, it should be played quickly. The potential cost of not being in a position to attack is often outweighed by the benefit of attacking a defence that is not yet set.

EMBEDDING PLAYS, PRE-SESSION

- Video clips are sent out and players are told what to look for

- Indoor meeting: The clips are replayed and players are asked what pieces of information they need to know to run the play

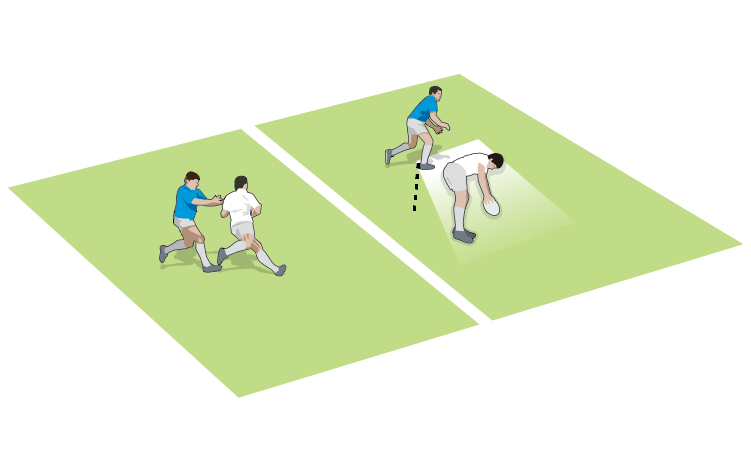

- Outside session: Walk through the play, then do a semi-opposed run through

Be a more effective, more successful youth rugby coach

- Win more games, without sacrificing the crucial element of fun

- Develop every player, regardless of vast differences in ability

- Run a respected, professional programme - even with a full-time job and limited time

Subscribe for full access

Special Offer: Premium Annual – SAVE 40%

Offer ends January 31

Use code: JANSALE

Or register and unlock 2 free articles,

receive our weekly newsletter, and

get a FREE coaching e-book.

Or if you are already a subscriber login for full access.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.