You are viewing

1 of your 2 free articles

Concussion at grassroots – you are working alone too often

Though you may have been on the courses, it’s not you who has to get up-to-speed.

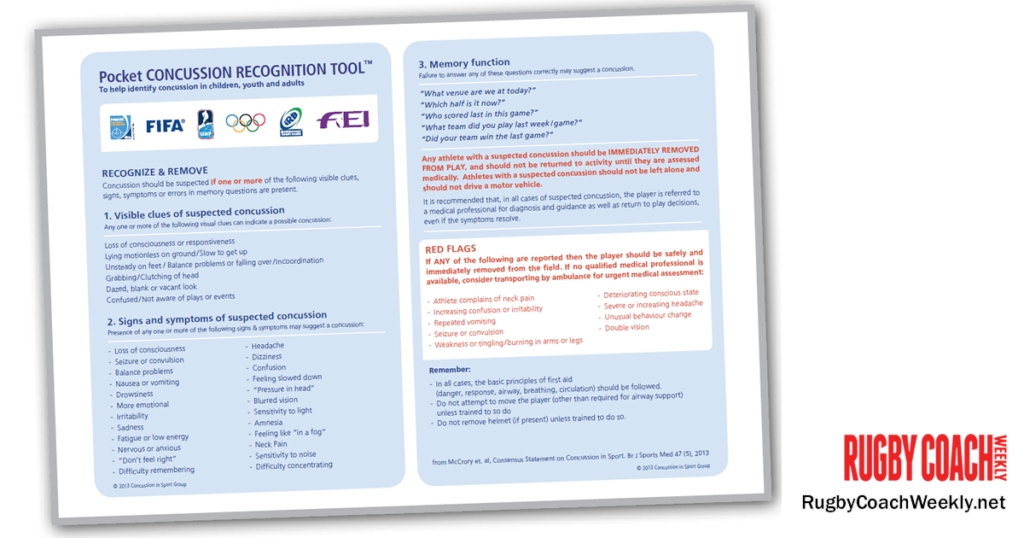

The framework provided to clubs includes such areas as concussion awareness indicators and “Graduated Return To Play” (GRTP)schemes, to help clubs deal with concussion in the most appropriate ways.

However, despite these excellent resources and help, down at the grassroots where players are not under the wing of a club on an almost daily basis, it has become clear that endeavouring to protect players as best as can be achieved is not as simple as it may be.

Community players especially at age group levels may only see their coaches once, maybe twice a week. Particularly at youth ages, players may well play for school sides as well as at a club.

Communication we would think would be the obvious path to ensure everybody protects a concussed player. But it’s equally clear that this doesn’t always work, as much because of ignorance of current guidelines, deliberate attempts to just ignore the issues, or the systems in place not dovetailing as neatly as needed.

The following are examples from some cases of concussion to players recently that have been reported to Rugby Coach Weekly.

CASE STUDY ONE

A player concussed in a school match displayed signs of concussion immediately. The parents contacted club coaches with concerns and were advised to seek medical attention as soon as possible.

Instead of taking the player to A&E they instead gave the player a favourite meal as a treat to cheer him up.

CASE STUDY TWO

A player concussed at a representative training camp showed no signs of concussion at the time but was sent home the next day by the school nurse who advised he seek medical attention.

His club was informed by his parents and a GRTP schedule drawn up. This was provided by his club to his school and the representative camp.

Clearly however, the club has no influence over either of them to insist GRTP is followed by them.

CASE STUDY THREE

A concussed player attended their doctor’s surgery for examination as advised, but was told the doctor did not handle such cases and was referred to an A&E department instead, which was 30 miles away.

CASE STUDY FOUR

A player that received concussion in a game was told by a team mate that if he told his coaches then they would not allow him to play, so to keep quiet.

CASE STUDY FIVE

Part of GRTP requires assurances that the player is well enough to firstly begin light training after a period of time, and finally to be signed off as fit to return to play.

A player seeking such medical approval has been told that by his doctor that this was a waste of medical resources.

CASE STUDY SIX

A player received concussion in a club game but showed no signs at that time. Within a few days the player suffered acute memory loss.

At a youth group, unconnected with sport, a volunteer who is also a nurse realised this acute memory loss and advised the parents to take the player to A&E. They did not. Neither did they inform the player’s coaches of the suspected concussion.

At the initial return to light training stage, the doctor’s approval was for full return to play. The player’s school, who were provided with the GRTP,

played the player in a match the next day.

The GRTP indicated the player still had over a week before possible return to full play dependent on medical approval at that juncture.

Our thoughts…

These separate and diverse examples indicate just how difficult it is for coaches to actually deal with concussion cases safely.They show that no matter how good the protocols are in place within a club or school, the second parties involved - the player and family, - and third parties - such as other squads and the medical system - also need to work with the

player’s best interests at heart – something that may not actually be happening.

Links to UNIONS’ guidance

World Rugby - playerwelfare.worldrugby.org/concussion

RFU - englandrugby.com/my-rugby/players/player-health/concussion-headcase

WRU - wru.co.uk/eng/development/medical/concussion.php

ARU - aru.com.au/runningrugby/PolicyRegister/ConcussionProcedureManagement.aspx

NZRFU - nzrugby.co.nz/rugbysmart/concussion

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.

More from us

© 2023 Rugby Coach Weekly

Part of Green Star Media Ltd. Company number: 3008779

We use cookies so we can provide you with the best online experience. By continuing to browse this site you are agreeing to our use of cookies. Click on the banner to find out more.