You are viewing

1 of your 2 free articles

Secrets of beating the best lineout operators

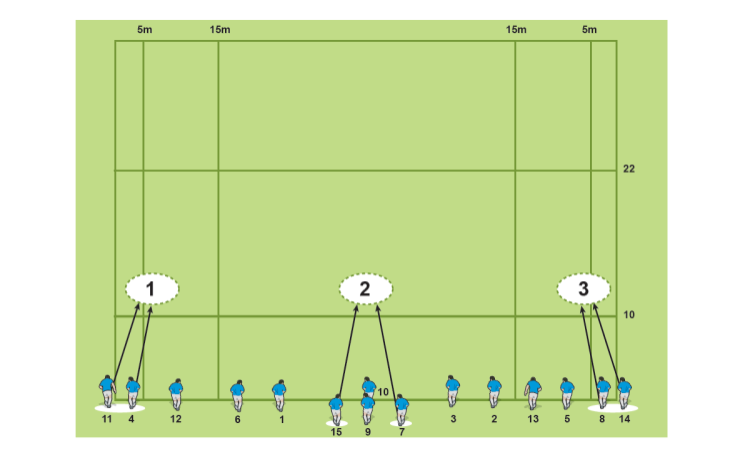

When opposed by an excellent lineout, you need to decide which areas of the lineout to defend, how to cover the vacuum at the back of the lineout and how to beat that lineout in attack.

I was the Springbok forwards coach when we had the likes of Victor Matfield in the team. But I was also advising his opponents, the Stormers in the Super Rugby competition. We had to formulate a plan to outplay the best lineout jumper in the world.

The most dangerous ball in the lineout is middle to back ball. It opens up the opportunity to pass the ball quickly into the back line, or peel around the back of the line into the soft underbelly of the space between 10 and the edge of the lineout.

A throw to the back of the line is the most risky throw because there is more chance of being inaccurate. So middle ball is the most likely and potent place in the lineout. This is where Matfield stood.

If the ball is going to the middle, he (or the player in his position), was likely to do one of three things. He would jump before the throw, wait for the throw and jump or move back for a lob throw. His skills were so good, that he was rarely beaten on the jump throw.

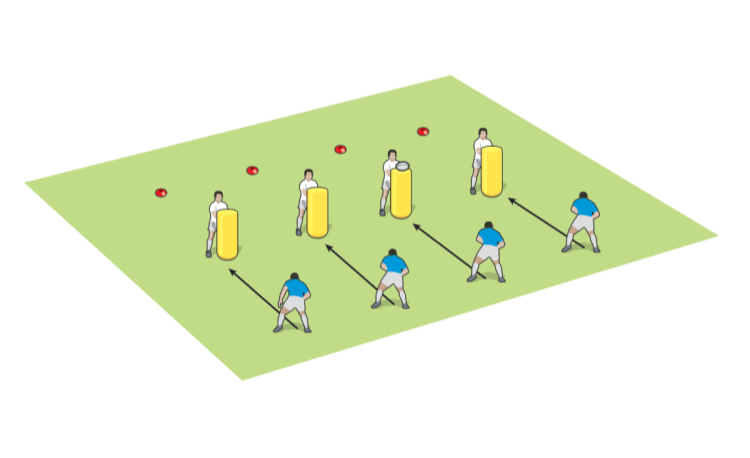

Teams can easily become a jack-of-all-trades when defending at the lineout. They have to work where they want to jump and how to cover the other areas. The Stormers, for instance, would tend to put their best jumping resources into the middle of the lineout.

In practice, they will defend against the three main jumping options (jump-throw, throw-jump and lob ball). They will then plan what will happen when and if this is not successful.

If you lose out at the lineout, you should have specific plans to cover the possibilities. No matter whether they jump in the middle or decide to challenge at the back of the lineout, always have a player at the back of the lineout. For the Stormers and Springboks, it was Schalk Burger. He, along with the other players at the back of lineout, will chase out into the midfield.

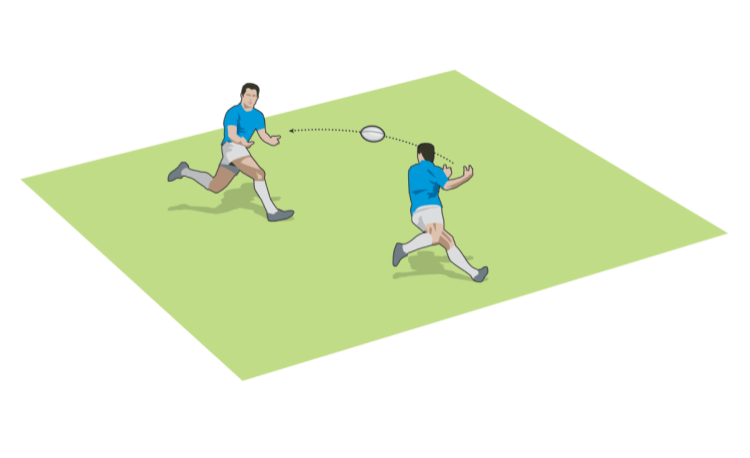

With the Stormers and the national team we reckoned that there is a vacuum at the back of the lineout and we need to cover this. The battle for the gain line is important. If the attacking backline can be over this line, then the forwards are in position to attack on the front foot.

Therefore we want our players out from the back of the lineout to run into their backline to hit their backs before they reach the gain line. In my experience, more teams are playing off the top of the lineout (throwing the ball down to the scrum half who then passes it away) to make the gain line. This makes the players at the back crucial. They cannot be tied up in jumping for the ball.

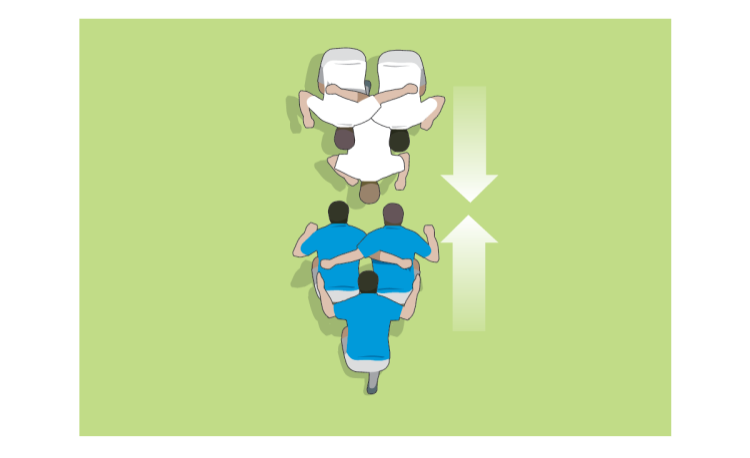

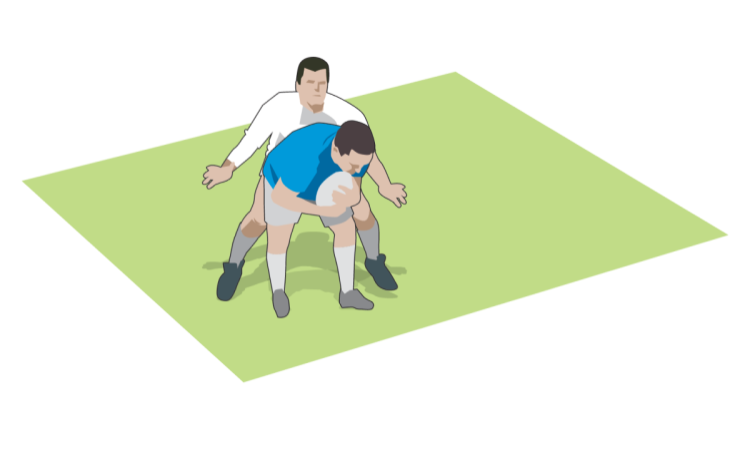

Catch and drive lineouts are used close to the scoring areas. This ball is not good for the backs to use because the defence can mark across from the midfield. Therefore we should be prepared to stop these players by pulling down the jumper before the maul forms.

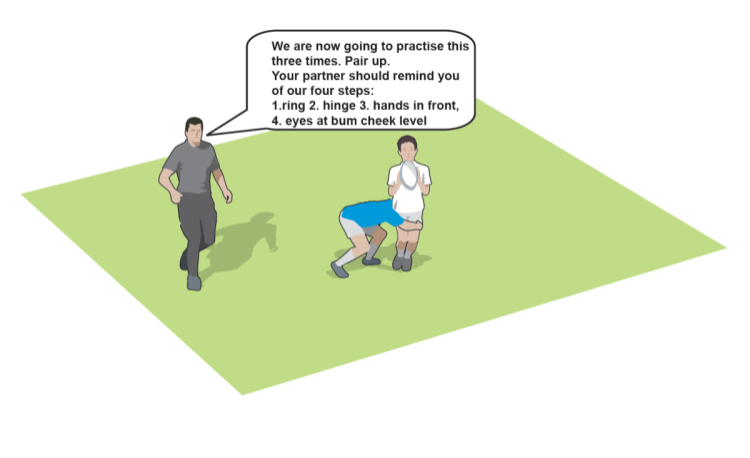

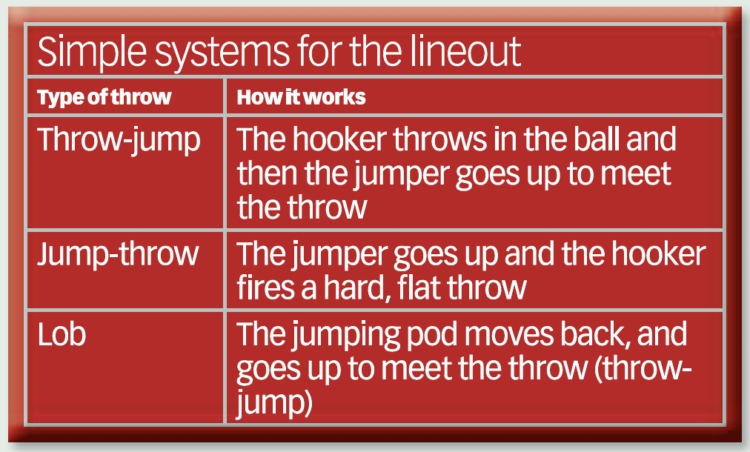

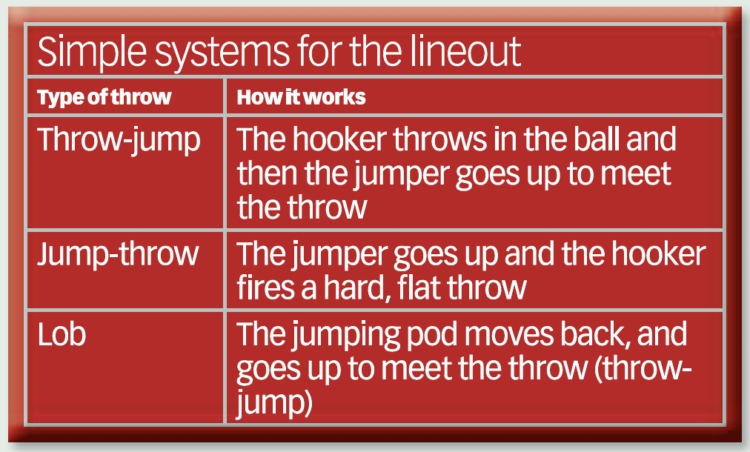

There are three main types of throw and jump combinations. Each has its strengths.

A throw-jump is where the hooker throws in the ball and the jumper takes his trigger from the throw, jumping to meet the throw. The ball tends to have a slight lobbed trajectory. The jumper knows he will have to reach higher to get the ball than a hard throw from the jump-throw.

A jump-throw has the jumper going up and then the hooker throwing in the ball. The throw is a hard flat throw. The jumper, like Victor Matfield, beats the opposition jumping pod into the air. His jump triggers a “rocket ball” throw.

The lob is a variation of the throw-jump, where the ball is thrown in with a looping trajectory. The jumper steps back about half a metre and takes the throw behind the opposition pod marking him.

Which throw you use depends on how the opposition pod is marking your jumping pod.

If the opposition jumper is watching your jumper, then he will not be watching the hooker throw. Therefore you should use the throw-jump. The throw comes in and then your jumper jumps to meet the ball.

The reaction time of the opposition jumping is based on the trigger of the jumper going up. A good jumper will be up before this pod, so the ball will meet the jumper before the opposition pod is up.

If the opposition jumper is watching the hooker throw for a trigger, then you should use the jump-throw. The jumper goes up and the hard, fl at throw gives the opposition no chance to beat the jumper to the ball.

If you are facing a team with a lean, quick jumper, who gets off the ground quickly, then a lob is best. The throw goes up, and so does the opposition pod marking your jumping pod.

However, the ball aims to go over the opposition jump. In the meantime, your jumping pod takes a step back and then jumps into the space behind the opposition pod. The ball drops into your jumper. Often a player like Victor Matfi eld is taking the ball at only three quarters of his normal jumping extension.

I was the Springbok forwards coach when we had the likes of Victor Matfield in the team. But I was also advising his opponents, the Stormers in the Super Rugby competition. We had to formulate a plan to outplay the best lineout jumper in the world.

IDENTIFYING THE MOST DANGEROUS ATTACKING LINEOUT

The most dangerous ball in the lineout is middle to back ball. It opens up the opportunity to pass the ball quickly into the back line, or peel around the back of the line into the soft underbelly of the space between 10 and the edge of the lineout.

A throw to the back of the line is the most risky throw because there is more chance of being inaccurate. So middle ball is the most likely and potent place in the lineout. This is where Matfield stood.

If the ball is going to the middle, he (or the player in his position), was likely to do one of three things. He would jump before the throw, wait for the throw and jump or move back for a lob throw. His skills were so good, that he was rarely beaten on the jump throw.

ALLOCATING THE RIGHT RESOURCES

Teams can easily become a jack-of-all-trades when defending at the lineout. They have to work where they want to jump and how to cover the other areas. The Stormers, for instance, would tend to put their best jumping resources into the middle of the lineout.

In practice, they will defend against the three main jumping options (jump-throw, throw-jump and lob ball). They will then plan what will happen when and if this is not successful.

LOSING THE BALL

If you lose out at the lineout, you should have specific plans to cover the possibilities. No matter whether they jump in the middle or decide to challenge at the back of the lineout, always have a player at the back of the lineout. For the Stormers and Springboks, it was Schalk Burger. He, along with the other players at the back of lineout, will chase out into the midfield.

With the Stormers and the national team we reckoned that there is a vacuum at the back of the lineout and we need to cover this. The battle for the gain line is important. If the attacking backline can be over this line, then the forwards are in position to attack on the front foot.

Therefore we want our players out from the back of the lineout to run into their backline to hit their backs before they reach the gain line. In my experience, more teams are playing off the top of the lineout (throwing the ball down to the scrum half who then passes it away) to make the gain line. This makes the players at the back crucial. They cannot be tied up in jumping for the ball.

Catch and drive lineouts are used close to the scoring areas. This ball is not good for the backs to use because the defence can mark across from the midfield. Therefore we should be prepared to stop these players by pulling down the jumper before the maul forms.

DETAIL OF THROW-JUMP COMBOS

There are three main types of throw and jump combinations. Each has its strengths.

A throw-jump is where the hooker throws in the ball and the jumper takes his trigger from the throw, jumping to meet the throw. The ball tends to have a slight lobbed trajectory. The jumper knows he will have to reach higher to get the ball than a hard throw from the jump-throw.

A jump-throw has the jumper going up and then the hooker throwing in the ball. The throw is a hard flat throw. The jumper, like Victor Matfield, beats the opposition jumping pod into the air. His jump triggers a “rocket ball” throw.

The lob is a variation of the throw-jump, where the ball is thrown in with a looping trajectory. The jumper steps back about half a metre and takes the throw behind the opposition pod marking him.

WHY IS THE BACK OF THE LINEOUT BALL SO POTENT?

- When the scrum half takes the ball, he is closer to the back line.

- Easier to peel round the back of the lineout into the 10m gap between the lineout and their backline.

- It is often the least well defended.

ATTACKING THROW AND JUMP TACTICS

Which throw you use depends on how the opposition pod is marking your jumping pod.

If the opposition jumper is watching your jumper, then he will not be watching the hooker throw. Therefore you should use the throw-jump. The throw comes in and then your jumper jumps to meet the ball.

The reaction time of the opposition jumping is based on the trigger of the jumper going up. A good jumper will be up before this pod, so the ball will meet the jumper before the opposition pod is up.

If the opposition jumper is watching the hooker throw for a trigger, then you should use the jump-throw. The jumper goes up and the hard, fl at throw gives the opposition no chance to beat the jumper to the ball.

If you are facing a team with a lean, quick jumper, who gets off the ground quickly, then a lob is best. The throw goes up, and so does the opposition pod marking your jumping pod.

However, the ball aims to go over the opposition jump. In the meantime, your jumping pod takes a step back and then jumps into the space behind the opposition pod. The ball drops into your jumper. Often a player like Victor Matfi eld is taking the ball at only three quarters of his normal jumping extension.

SUMMARY

- You cannot cover all the threats in the lineout.

- Identify their most lethal threat and mark that area the most.

- Work out the defence plan if the ball is lost or the ball is not thrown to that area.

- Always cover the back of the lineout with a player on the ground.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.